A few years ago, the meditation app I used was outmoded by an iOS update and the following warning appeared every time I used it.

Most of the technology we use helps us do things better and faster. A car gets us where we're going with freedom and speed. A microwave cooks food in minutes, where if we used a stove or, even slower, an open fire, it could take hours. An email sends a message in seconds. If we were to put that message in the mail instead, we'd wait days for it to arrive. If we carried it by hand, or even on a pony like they used to, it could take a very very long time.

But valuing faster and better above all else creates a way of life that can miss out on life itself. For example, think of all the things you speed past in a car on your way somewhere. Or, think of all the things you might see and learn and do if you walked instead. Think of the learning that happens when you burn something you've cooked, or the primal and empowering experience of building a fire. Think of how differently you’d write an email if it took massive effort to get it to someone. Technology, which was born out of industry, war, and office environments, rightly prizes efficiency and function, but somehow we haven't fully integrated the fact that we live significant parts of our lives in homes and backyards, families and friendships.

A concept I've been reading about lately, slow technology, challenges these values and asks the question, what if we designed technology for the experiences we have while using it? What might change if we reconsidered the idea that everything needs to get done as quickly as possible? Lars Hallnäs, a well known researcher of slow technology, has a popular paper he wrote with Johan Redström called Slow Technology — Designing for Reflection. There's also paper that's barely been cited that I really like, On the Philosophy of Slow Technology. I’ve recently read both (plus a few others) and I'd like to use this post to share what I currently understand about slow technology — both as an exercise in my own learning and also to serve as a reference in the future when I discuss the concept in panels and presentations. Prepare to dive into some specifics here, but trust me to not be overly academic about it.

There are three concepts I think are important to understand when it comes to slow tech:

Slow tech is not developed, it is enveloped.

Slow tech values different things than we're used to.

Slow tech may be beneficially frustrating.

DEVELOPMENT vs. ENVELOPMENT

When technology is developed, it is solution-oriented.

We have a problem:

getting from here to there

feeding ourselves

communicating w/someone far away

Technology solves it:

with a car

with a microwave

with an email

But when technology is enveloped, it is experience-oriented. We consider things beyond what it would take to send a message, feed ourselves, or get us here from there as quickly as possible. Instead of saving every bit of time we can, we intentionally fill it with playful, reflective, or profound experiences enabled by technology. With slow technology, we can ask how the experience of using technology enhances our lives. It's not what the technology does, it’s who, how, and what we are while doing things with it.

VALUES

When technology is enveloped, it's like we draw a big circle around our use of it and everything in that circle becomes alive and worthy. Hallnäs points out that normally, we don't value anything inside the circle if it's not efficient or functional, but he suggests that there are all sorts of valuable things inside. For example:

We might value understanding how the technology works and why it does what it does.

We might value how the technology inspires or requires us to reflect on it (or ourselves).

We might value being thoughtful about how we apply or use the technology.

We might value increasing our awareness of the consequences of technology.

We might value craft — our masterful and artful use of a technology.

When we value things like reflection or craft — when efficiency or ease of use is not our number one value — we design technology differently. In fact, we might design it to be purposefully difficult or mysterious. Why would we do this? Because the experience of being human is not a race to the end of our lives. We might consider designing technology and tools so that the use of them gives us meaning along the way.

BENEFICIALLY FRUSTRATING

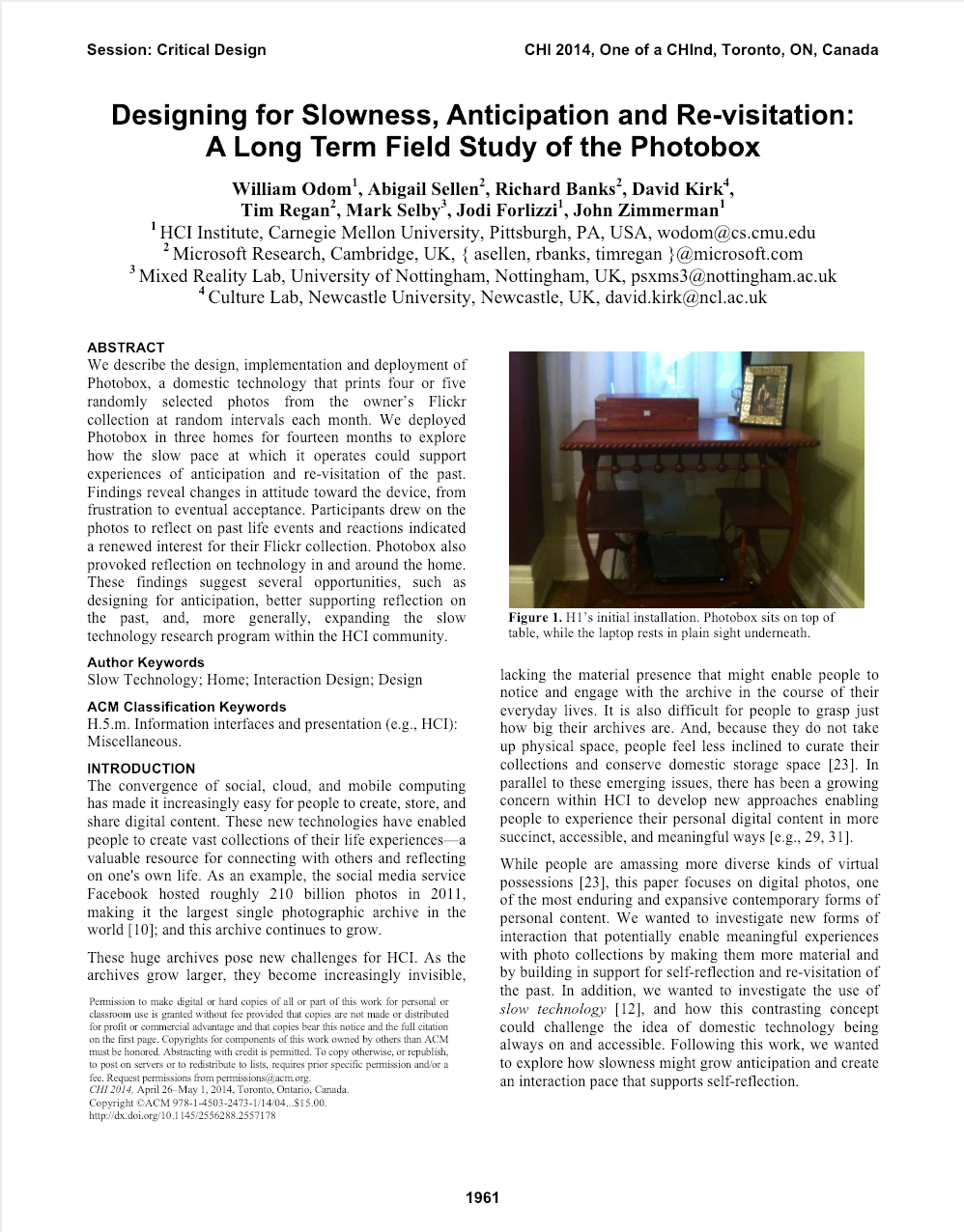

Another well known researcher of slow technology is Will Odom. He wrote a paper about design called, Designing for Slowness, Anticipation and Re-visitation: A Long Term Field Study of the Photobox that explores what we do when we encounter and live with a slow technology.

The Photobox is a wooden box that sits in a prominent space in a home and every once in a while, it quietly prints a photo from the digital photo archive of the people who live there. They open the lid, look for a photo, and usually don't find one, but every once in a while (four or five times a month), they do.

Odom studied how folks experienced having the Photobox in their homes for over a year and he found that at first people were excited and eager to use the Photobox, but they soon became frustrated because of how slow and recalcitrant it was. This frustration lasted up to six months for some. Eventually, though, all households (admittedly there were only three), arrived at a place of acceptance and appreciation of the Photobox and its slow and random ways.

Perhaps more importantly than feelings like excitement, disappointment, frustration, and acceptance, were the lived experiences that accompanied them. First, users had to be with their emotions. Short of chucking the Photobox out a window, their impatience had no recourse with the machine. And when new photos arrived, some were surprised by images they'd long wished to forget and they had to experience that. One user began to put the photos under her pillow, another couple put them on their fridge. The device gave presence and potency to photos of a former life lived, enabling thoughtfulness and reflection — all arguably good things that may never have been possible with a “fast” approach.

THIS APP MAY SLOW DOWN YOUR IPHONE

While I tend to be cynical about technology doing much good in a marketplace that ruthlessly vies for our attention and manipulates our behaviors and attitudes (more on this joyful topic, soon!), the idea of slow technology is inspiring to me. It makes me wonder what it would be like to have technology on my side instead of constantly wrestling with it to achieve my goals of being self-aware, loving, and present to my life while living it.

The following papers might be fun to dig into if you’re the sort to do such things…

Hallnäs, L. (2015). On the Philosophy of Slow Technology. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae-Social Analysis, 5(1). Retrieved from http://www.acta.sapientia.ro/acta-social/C5-1/social51-03.pdf

Hallnäs, L., & Redström, J. (2001). Slow technology--designing for reflection. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(3), 201–212.